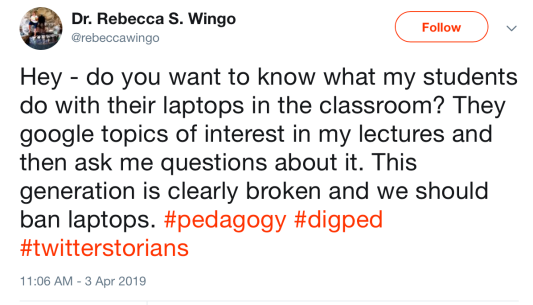

Thoughts prompted by this excellent tweet and conversation:

I’ve been working as an academic technologist at a university for almost two years. I could retire if I got a dollar for every time I’ve heard complaining about how students can’t handle having computers/laptops in the classroom.

Thankfully, there are people like Rebecca Wingo to make me feel all better. Look at this productive, pedagogically appropriate use of laptops in a classroom. Encouraging students to validate what they’re hearing, to confirm facts, to find additional resources. THAT is what technology can do when used appropriately.

Photo by John Schnobrich on Unsplash

I was teaching in a class recently. Students were assigned to do research and develop a digital project in the space of three class periods. They had class time to do this. They were in small groups of 2 to 3. For an entire class period (75 minutes), these students were focused, productive and above all, learning. What types of learning did I see?

- Content: they learned essential content about their chosen topic of interest

- Group work: they were working in small groups, they had to divide tasks, resolve any disagreements

- Time management: they only had two class periods to do this project. The weren’t supposed to work on it outside of class. They couldn’t be distracted

- Digital literacy: they learned how to find information and decide if it was valid, reliable, useful

- Digital skills: they had to try a new digital tool and master it in a short period of time. It was not complex, but did require them to create and share a Google Sheet (this was new to some); learn a template and publish it within the other tool.

- Writing: they had to quickly find, digest and communicate information. This was done through digital appropriate writing (much different than academic!)

- Visual communication: they were required to use visuals and possibly spatial data. Using these different types of media can be challenging. Copyright, interpretation, technical skills all come into play.

I sat in and helped as needed for all three sessions. I did not see a single student “distracted” by the technology. They were on task, they were focused and they created something. They looked at content differently. They discussed. I saw a few kids send a few texts. but they got right back to work. Did they create something like a 10-page final paper? No. And I bet they’ll remember it far longer than the 10-page paper they wrote for another class.

What made this a such a successful project? In my mind, it was a few things:

- Students were actively engaged in their learning.

- Students produced something, not just absorbed information.

- Students were learning about something of their choice.

- Students were helping each other learn new things.

- Students were given permission to fail, or to not be as perfect as an A usually requires.

- Learning was more about the process than the final product.

While my example is quite different than the one Rebecca Wingo shared in her tweet, it’s fresh in my mind.

For my next lecture, however, I am going to purposefully toss a few things in to have students engage. I do love the look on students’ faces when you tell them to get out their phone/laptop. It’s even more rewarding when the “students” are faculty/instructors. I often present to faculty/instructors about incorporating technology into classes, whether it’s the learning management system, Google, GIS or something else. I usually do incorporate some sort of hands on tech thing, since that what I’m teaching, but after Rebecca’s post, I am going to be even more deliberate to model what they can do with students in class.

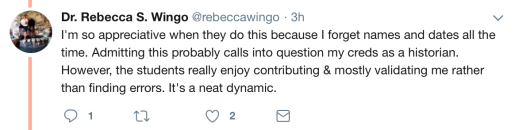

Cred

I almost forgot — I wanted to address the thought that forgetting names/dates and having students look up things calls into question her credibility. I think it’s quite the opposite. She’s teaching them so much more about how to be a historian, how to study history and how to be a student. I hope our credibility as historians (or other subject matter experts) isn’t on how much we can memorize and spit back. It should be on how we can find information, analyze, conceptualize, and more. I’m even more impressed in her credibility!